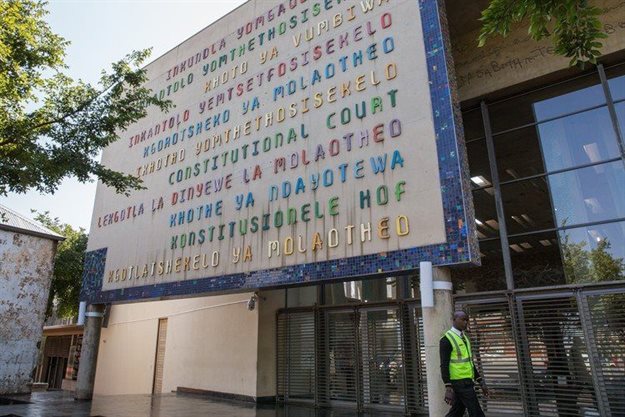

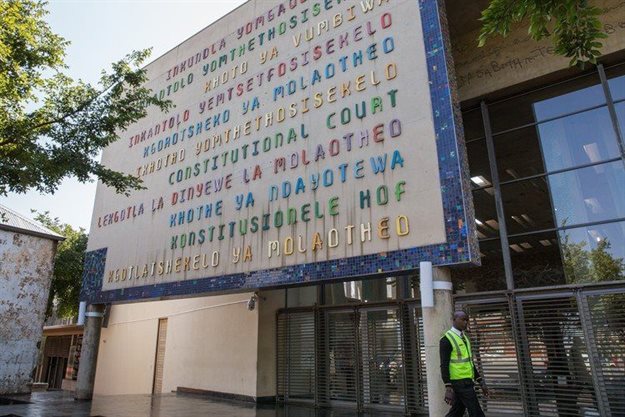

The Constitutional Court ordered the appointment of a special master to assist the Department of Rural Development and Land Reform to process a huge backlog of claims. Photo: Ashraf Hendricks

A labour tenant is someone who works on a farm in exchange for the right to live on that farm and work a portion of the farm for him or herself (source: LARC). In pre-constitutional times, they were at the mercy of the landowner who could withdraw permission to live and work on the land at will. The Constitution guaranteed not only that they had rights to the land independent of the owner, but even provided an opportunity for them to claim ownership of the land where appropriate.

A special master is an external person with appropriate expertise appointed by the court to assist the Department of Rural Development and Land Reform to devise a plan for the department to process labour tenants’ land claims.

Before 31 March 2001 thousands of labour tenants had lodged applications under the Labour Tenants Act for security of tenure and restoration of ownership. Where applications were opposed and the matter could not be settled, the department had to refer the matter to the Land Claims Court. But, the department simply failed to do so.

For example, some labour tenants, who were party to the Constitutional Court case, had claimed a portion of land on Hilton College property – one of the most expensive schools in the country. After mediation between the labour tenants and Hilton College failed, the department failed to refer the matter to the Court, leaving the tenants waiting for over 20 years.

The first applicant, Bhekindlela Mwelase, a labour tenant living on Hilton, was 82 when the case was launched in 2013. He died six months before the Constitutional Court hearing on 7 November 2018. The second and fourth applicants were representatives of labour tenants who died in the 2000s while still waiting for the department to process their claims.

The court heard that while the department was not even able to provide information as to how many claims were actually outstanding, a figure of 11,000 was realistic.

The Association for Rural Advancement (AFRA) represented by the Legal Resources Centre (LRC) launched litigation at the Land Claims Court in 2013 after it became apparent that the department was failing to finalise labour tenant land claims.

In the Land Claims Court, the department made the extraordinary claim that, while it was aware of its statutory duties to process these claims, it had decided to abandon this duty because “it considered it was better placed to know what labour tenants needed, and to decide what they would get [...] The department in effect conceded its statutory duties under the statute – but suggested that it knew better than the legislature,” noted the judgment.

The Land Claims Court ordered that a special master for labour tenants be appointed to assist the department to develop a comprehensive strategy for efficient processing and referral of claims.

The department appealed to the Supreme Court of Appeal (SCA) in 2016, arguing that the appointment of a Special Master violated the principle of the separation of powers: the judiciary should not stray into the lanes of the legislature or the administration. For the Court to appoint a person to assist and oversee the department, it was argued, goes too far. The SCA sided with the department and overturned the Labour Claims Court’s appointment of a special master, finding that it was not necessary or appropriate for the courts to oversee the running of the department. It said it was a “textbook case of judicial overreach” because, for example, the special master might take over the responsibilities of the Director General and officials of the department.

Tuesday’s Constitutional Court judgment, written and read by Justice Edwin Cameron on the day of his retirement from the court, carefully considered not only the question of the separation of powers, but also the introduction of a new concept, that of the special master, into South African law.

While it was important to respect the separation of powers as mentioned by the Supreme Court of Appeal, the court found, this does not imply such a strict separation between the branches of government that they can never cooperate towards “fulfilling practical constitutional promises to the country’s most vulnerable”.

While the court must and will only in extraordinary circumstances interfere in the business of another branch, “the department’s tardiness and inefficiency in making land reform and restitution real has triggered a constitutional near emergency”. In these circumstances, it is justified. In any event, the Labour Claims Court will retain full control over the special master because it controlled the scope of work.

“Where egregious infringements have occurred, the courts have had little choice in their duty to provide effective relief,” read the judgment.

The appointment of a special master recognised the joint responsibility to sustain and strengthen growing institutions, read the judgment. It acknowledged judicial complicity in institutional and systemic dysfunction that often impedes achieving constitutional goals.

A minority judgment written by Judge Chris Jafta mostly agreed with the majority judgment, but argued that it went “beyond a constitutionally permissible intervention by a court in the performance of administrative functions”.

This article was originally published on GroundUp.