How land reform and rural development can help reduce poverty in South Africa

The country’s poverty levels have increased sharply over the past five years with an additional 3-million people now classified as living in absolute poverty. This means about 34-million people from a population of 55-million lack basic necessities like housing, transport, food, heating and proper clothing.

Much of the commentary on these sad statistics has emphasised the poor performance of urban job creation efforts and the country’s education system. Little has been said about the role of rural development or land reform.

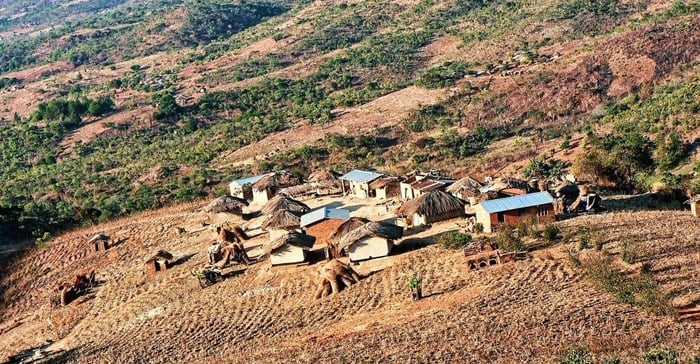

This is a major omission given that about 35% of South Africa’s population live in rural areas. They are among the worst affected by the rising poverty levels.

Large tracts of land lie fallow in the country’s rural areas, particularly in former homelands (surrogate states created by the apartheid government). They were fully integrated into South Africa in 1994 bringing with them large amounts of land under traditional authorities.

Research by the Human Sciences Research Council suggests that poverty levels can be pushed back significantly if policies are put in place that focus on food security and creating viable pathways to prosperity for the rural poor. This would be particularly true if land reform helped people develop the means of producing food, generating value and employing people.

The problem

Researchers investigating the land needs of marginal communities, such as farm workers and rural households in the former homelands, have uncovered a considerable desire for opportunities on the land.

But they found that municipalities, government departments and banks were offering relatively little assistance to poorer would-be farmers seeking to improve their land and its value.

In the former homelands in particular, many families reportedly felt opportunities existed literally on their doorsteps but they lacked the means and support to grasp them. A common response among young people to the absence of such opportunities is to pick up and leave for the cities.

The need to rekindle rural development in South Africa is widely recognised even within the government. The country has lots of policies that speak to the ideal of lifting the rural poor out of poverty. Some policies are just not followed while others have proven to be inappropriate.

A fundamental problem underpinning successive rural development initiatives has been the split between the two main strands of government land reform policy: land restitution and land redistribution.

Land restitution was largely conceived as a means of addressing the colonial legacy of land dispossession. For its part, land redistribution was mainly designed to create a new class of black commercial farmers who would inherit existing white commercial farms.

Neither has been successfully implemented. Land restitution has been painfully slow, while land redistribution has been criticised for becoming increasingly elitist.

To advance land redistribution the government put in place a land acquisition strategy that acted as an enabler for entrepreneurs who wanted to get into large-scale, commercial agriculture. Once again the poor were left at the margins.

In the early years of democracy, the African National Congress adopted a “do no harm” approach in relation to land tenure in the former homelands. The reasoning was that this land served as a bulwark against poverty.

But that policy appears to have shifted to focus on bolstering the power of local chiefs to oversee land use. The ruling party is leveraging the clout of the chiefs to secure rural constituency support during elections.

A sharp historical irony is that the present government is arguably reproducing patterns of land ownership that were originally justified by the colonial ideology.

What must be done

A range of different models could be adopted in different localities. Recently there’s been a significant rise in the establishment of informal land markets.

This indicates that disregarded rural land has substantial value. But this value is being undermined by a lack of appropriate titling opportunities and land management systems.

What is required is a single and inclusive land reform programme. It must view all land as economically valuable and aim to maximise its potential without undermining people’s social and cultural rights and expressions of identity and belonging. Such a programme should recognise that unused land can be used to address poverty and stimulate growth if it is incorporated into rural value chains.

![]() And to make farming easier and more worthwhile new mechanisms and arrangements must be designed to release productive land currently locked up in customary practices. Although individualist freeholding is an inadequate and often wildly inappropriate alternative to present tenure practices, chiefs and communities should be held accountable if they appear unable to improve their land.

And to make farming easier and more worthwhile new mechanisms and arrangements must be designed to release productive land currently locked up in customary practices. Although individualist freeholding is an inadequate and often wildly inappropriate alternative to present tenure practices, chiefs and communities should be held accountable if they appear unable to improve their land.

Source: The Conversation Africa

The Conversation Africa is an independent source of news and views from the academic and research community. Its aim is to promote better understanding of current affairs and complex issues, and allow for a better quality of public discourse and conversation.

Go to: https://theconversation.com/africa