Image: Former Eskom CEO Andre de Ruyter | PenguinRandomHouse

Dirt piled up at even the newest power stations until it damaged equipment, which stopped working – and some equipment disappeared beneath a layer of ash.

Integrity had been displaced by greed and crime:

Corruption had metastasised to permeate much of the organisation.

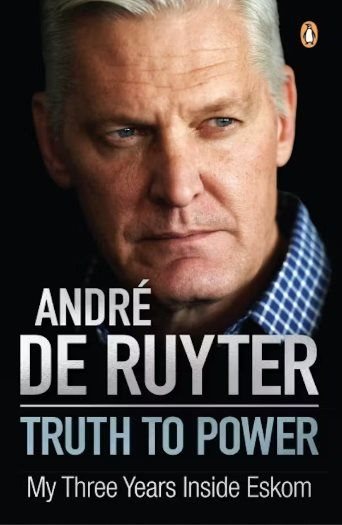

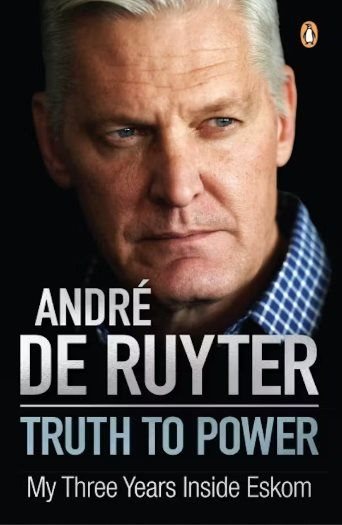

As a political scientist who has, among other topics, followed corruption and kleptocracy, this book ranks among the more informative.

De Ruyter (or his ghost writer) delivers a pacey, racy adventure thriller. Chapter after chapter reads like a horror story about Eskom, whose failure to generate enough electricity consistently for the past 15 years has hobbled the economy.

The book is also a sobering indication that parts of South Africa now fester with organised crime.

This book merits its place alongside How to Steal a City and How to Steal a Country. These two books chronicle how corruption undermined respectively a city and a country to the level where they became dysfunctional.

Brazen looting

Another take-away is the devastating indictment of De Ruyter’s immediate predecessors as CEO, Matshela Koko and Brian Molefe. They appear as incompetent managers who ran into the ground what the Financial Times of London had praised as the world’s best state-owned enterprise as recently as 2001. Both Koko and Molefe have been charged with corruption – at Eskom and the transport parastatal Transet, respectively.

The standard joke about corruption is “Mr Ten Percent” – meaning a middleman who adds 10% onto the price of everything passing through his hands. Under Koko and Molefe, this had allegedly ballooned into “Mr Ten Thousand Percent”.

For example, De Ruyter writes that Eskom was just stopped in the nick of time from paying a middleman R238,000 for a cleaning mop.

Carien du Plessis 26 Apr 2023

Corruption focused on the procurement chain. One middleman bought knee-pads for R150 ($7,80) and sold them to Eskom for R80,000 ($4,200). Another bought a knee-pad for R4,025 ($209) and sold it to Eskom for R934,950 ($48,544). The same applied to toilet rolls and rubbish bags. One inevitable consequence of corruption on such a scale was that Eskom’s debt, which was R40bn ($2.076bn) in 2007 (the year that former president Jacob Zuma came to power), ballooned to R483bn ($25bn) by 2020 – which incurred R31bn ($160m) in annual finance charges.

Image: PenguinRandomHouse

De Ruyter reveals that the “presidential” cartel (meaning one of the local mafias) pillaged Matla power station, the “Mesh-Kings” cartel Duvha power station, the “Legendaries” cartel Tutuka power station, and the “Chief” cartel Majuba power station. He writes that the going rate for bribes at Kusile power station is R200,000 ($10,377) to falsify the delivery of one truckload of good quality coal. Kusile is one of the two giant new coal-fired power stations which Eskom is relying on to end power cuts.

The book says a senior officer at the Hawks, the police’s priority crimes investigation units, tipped off De Ruyter how he was blocked in all his attempts to combat corruption at Eskom. Senior police officers, at least one prosecutor, and a senior magistrate, have also been bribed by the gangs.

Noncomformist

Eskom had 13 CEOs and acting CEOs in 13 years. Twenty-eight candidates, most of them black, rejected head-hunters’ offers to become CEO of Eskom. De Ruyter who was previously CEO of Nampak, took a pay cut (to R7m) to accept the job, in the hope of accelerating Eskom’s transition from coal to renewables.

Bhargav Acharya 23 Feb 2023

At the time of his appointment some commentators alleged that he was an African National Congress (ANC) cadre deployed to Eskom. The ANC’s cadre deployment policy is aimed at ensuring that all the levers of power are in loyal party hands – often regardless of ability and probity. But De Ruyter came into conflict with the ruling party.

What caught De Ruyter out was the viciousness of the political attacks on him: smears of racism and financial impropriety. He had to devote many hours of office time to refuting them:

occupying that seat at Megawatt Park comes with political baggage.

Megawatt Park is Eskom’s head office in Johannesburg.

The book’s early chapters summarise how he was one of those Afrikaners with Dutch parents, who did not conform entirely to apartheid norms. The Afrikaner volk imposed the apartheid regime onto South Africa for 42 years. In his high school years he became a card-carrying member of the Progressive Federal Party, a liberal anti-apartheid opposition party, antecedent of the Democratic Alliance, which is now the official opposition to the governing party.

Poisoning

De Ruyter’s book mentions organising a routine Eskom stakeholders’ meeting at a guesthouse in Mpumalanga province.

To save time, he ordered that food be served on plates to table places, instead of buffet arrangements. The guesthouse management refused, due to fear of facilitating poisoning one or more guests – only buffet arrangements could thwart that.

He says that in Tshwane (Pretoria), the seat of government, the National Prosecution Authority no longer orders takeaway lunches for delivery to their premises. Instead, standard procedure is that a staff member buys lunches for all at random take-away shops.

This sinister development culminated in De Ruyter himself being poisoned with cyanide in his coffee in his office, demonstrating how mafia-type gangs had recruited at least one Eskom headquarters staff member.

Unintended consequences

In several places De Ruyter also touches on other issues. The unintended consequence of some government policies, such as localisation and preferential procurement, is that it costs Eskom two and a half times more to pay for each kilometre of transmission cable than it costs Nampower Namibia’s power utility, just across the border.

What stands out from this memoir is that the success of a company demands that a CEO, managers, artisans, guards, and cleaners all take the attitude that the buck stops with them – seven days a week – and act accordingly.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.