More recently, Brad Pitt has taken an interest in architecture. His support for the construction of new homes in New Orleans – via his Make It Right foundation – following Hurricane Katrina has continued to keep social and environmental concerns in the public eye. Clearly, this is a worthwhile endeavour, and hard to fault.

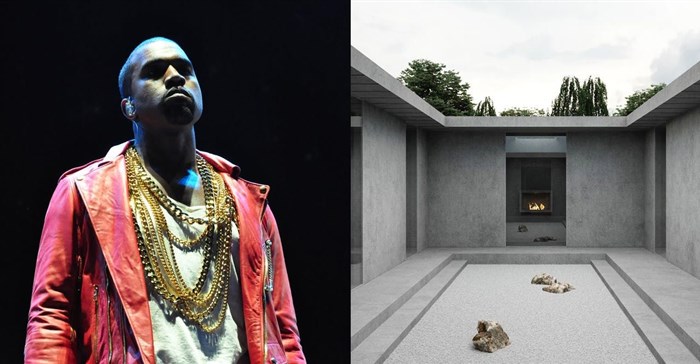

Now entering the arena is Kanye West, who recently announced on Twitter that his company Yeezy would be branching out into architecture. Early visualisations of West’s collaboration with architects Jalil Peraza and Petra Kustrin and 3D artist Nejc Škufca suggest the first project will be a prefabricated concrete “low income” housing scheme, arguably designed in a Brutalist style.

Questions arise, perhaps not least regarding whether the self-proclaimed polymath genius is the right person to create social housing for the masses. As a professor of urban design, it’s not immediately clear to me how the competing forces of real estate, fame and social concerns can be remixed to blend harmoniously in the modern urban landscape.

Form over content?

By putting his weight behind this project, West has drawn much-needed attention to a critical issue in a society that, for many years, allowed housing to divide communities and determine social status. In the US, public housing projects are much maligned – sometimes referred to as “the housing of last resort”. If West wants to enhance the reputation of public or affordable housing as something residents can take pride in, then his intentions are admirable.

But with Kanye West, the message can always overtake the medium. With typical bombast he has said:

I’m going to be one of the biggest real-estate developers of all time – what Howard Hughes was to air crafts and what Henry Ford was to cars … We gonna develop cities.

Having purchased 300 acres of land to develop five properties, it certainly seems he is committed to the idea at some level.

It may be unhelpful, at some level, to criticise West’s motives – but we can and should question the potential outcome. As West told a group of Harvard students: “I really do believe that the world can be saved through design, and everything needs to actually be ‘architected’.”

On the plus side, this kind of vision along with West’s high level connections, considerable resources and sheer force of personality could enable this development to actually happen – which, since the demolition of the dilapidated and crime ridden Pruitt-Igoe project of St Louis, Missouri in 1973 further plunged the public view of mass housing into disrepute, is no small achievement.

Yet West is seemingly impervious to constructive criticism or capable of being managed – as he has even said himself. We can reasonably assume community engagement and participatory processes will go out of the window. These are essential for public housing, especially in the US where their omission has contributed to terrible living conditions.

In their place, his love for the people is expected to be met by the appreciation and gratitude of the masses. His embrace of disruption does not acknowledge the consequences – in a lot of cases, innovation fails to favour people living on low incomes. In the context of urban design, putting in place infrastructure such as train tracks and highways has typically served to provide sharp boundaries between different communities.

Hashtag ignorance

Recent outbursts – such as his statement regarding slavery being a choice – have done little to display his ability to understand the very people the Yeezy Home is being designed for. Further, his unwillingness to grapple with the complexity of politics and racism endemic in US urban development only highlight how removed from history and society he actually is.

Megalomaniacs have produced many visions for cities over the years, with mixed results: consider the contrasting schemes of Swiss Modernist architect Le Corbusier or Hitler’s personal architect Albert Speer, in their respective quests for a new urbanism. The neo-Brutalist aesthetic of the Yeezy homes is a sideshow in this arena, an Instagram-ready shorthand for contemporary cool. The real story is the grand vision into which the housing sits.

With West’s drive to build his utopia on behalf of others, while skirting around inconvenient issues such as social equity, spatial justice (determined by access and proximity to essential services, public funds and other features) and urban history, his success will be immense – just not in the way he imagines it.

By designing for – rather than with – people, ignoring important social and urban developments and assuming the role of great benefactor, West would enter the history books – but not as a pioneer for social good or innovative design. Instead, he would join an already crowded history of urban developers who designed black people out of the landscape.

For this particular entanglement of social housing and celebrity endorsement, the future of the Yeezy Home project looks likely to aid and abet gentrification processes, not resolve them. Another brand for him, in the guise of a concern for the many –– and that’s the brutal truth.

For this particular entanglement of social housing and celebrity endorsement, the future of the Yeezy Home project looks likely to aid and abet gentrification processes, not resolve them. Another brand for him, in the guise of a concern for the many –– and that’s the brutal truth.