Repetitive sounds and seizures experienced in infancy can permanently hinder formation of blood vessels in the brains of mice, Yale University researchers report online 4 December 2013 in the journal Nature.

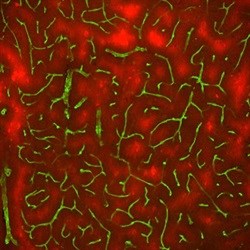

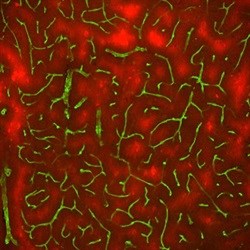

Excessive brain activity caused by stimuli such as repetitive sounds cause a reduction in blood vessels (green) in newborn mice and create areas of low oxygen content (red), Yale researchers have found. The researchers ask whether similar stimuli in human infants might cause long term damage in developing brains of human children.

click to enlargeThe findings raise an intriguing question, note the researchers: Can similar stimuli during infancy in humans, such as fever-related seizures and lengthy exposure to blaring music cause a long-term reduction in brain blood vessels?

"This could have negative repercussions in normal brain function and increase susceptibility to age-related brain disorders including cognitive decline," said Jaime Grutzendler, associate professor of neurology and neurobiology and senior author of the study.

Angiogenesis - or the formation of new blood vessels - occurs in the brain during embryonic stages and for a period after birth. Grutzendler and colleagues Christina Whiteus and Caterina Freitas wanted to know how the growing brain acquired an appropriate number of blood vessels after birth and whether brain activity influenced their growth.

In the study, researchers exposed the mice to repetitive sounds and exercises. They found that during the first month of life in mice - the equivalent of two years in humans - the formation of new blood vessels was almost completely blocked by these stimulations, specifically in areas of the brain that processed the repetitive stimuli. They also showed that repetitive stimuli increased cells' production of nitric oxide, which in turn caused the interruption of new vessel formation. Seizures also dramatically reduced the formation of blood vessels.

Interestingly, mice older than a month showed no ill effects from sounds, seizures, or prolonged exercise. However, in younger mice, the reduction in blood vessels was permanent and led to pockets of oxygen-deprived areas and affected the health of neuronal connections.

Scientists had known that excessive neural activity like seizures directly disrupted the development of neuronal connections. Although more study is needed, the new research shows repetitive stimulation also has a permanent effect on the blood vessels, making the brain potentially more susceptible to disease.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health.

Source: Yale University