Subscribe & Follow

Advertise your job vacancies

Covid-19: Why "test, test, test" is easier said than done

Testing people suspected of Covid-19 and then tracing who they have had contact with is vital to controlling the epidemic. But the test for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19, is both expensive and logistically time-consuming.

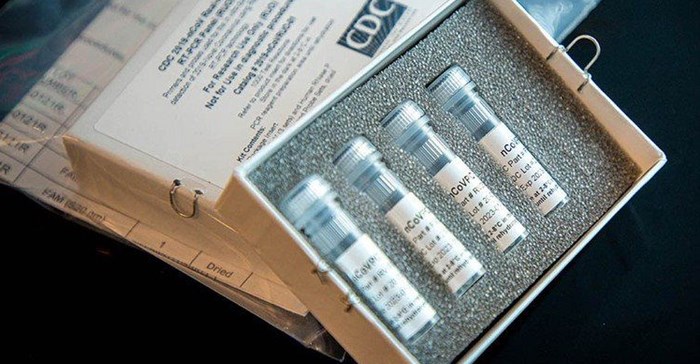

CDC 2019-Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Real-Time Reverse Transcriptase (RT)-PCR Diagnostic Panel. Photo: United States Centers for Disease Control via Wikimedia (public domain)

A complicated process

President Cyril Ramaphosa said on Sunday night that everyone returning back to South Africa from high-risk countries would get tested. This probably isn’t practical at the moment. Doctors we spoke to said the waiting time to get a swab taken from you at a private laboratory in Johannesburg was about half an hour and people had to be turned away at a state testing facility in Cape Town.

“It’s too much,” an infectious disease specialist told us. “We simply can’t test as much as South Korea.”

“I’d suggest that for now we test only people who are symptomatic and who have recent travel or contact with a confirmed case. That’s the National Institute for Communicable Diseases (NICD) recommendation. As the disease progresses, this may be loosened because we will assume everyone has had contact with an infected person.”

He emphasised that with limited resources, everything must be focused on sick people.

What’s in a test?

This is what’s involved in getting a test for the coronavirus that causes Covid-19:

First, a nurse or doctor takes a swab from you, preferably from your nose, which is usually the best place for getting the most virus. Swabs can also be taken from your pharynx, which can cause you to gag, or you can cough up sputum. If you watch videos of this being done, you’ll notice it’s not straightforward. The health worker taking the swab needs to wear a mask because of the possibility of you sneezing or coughing in his or her direction.

Then the swab needs to be taken to a lab quickly.

There a technician does what is called a polymerase chain reaction, or PCR, test on your swab. This test works by making copies of viral DNA till there’s enough to detect it. To do a PCR test you need a bunch of chemical reagents. For many infections, such as HIV, there are manufacturers around the world supplying kits with all the reagents the laboratory needs. But SARS-CoV-2 was only discovered a couple of months ago and as far as we can tell no such prepackaged commercial kit yet exists for it. So until such kits are available — which should be soon — laboratories have to source the various chemicals, using a protocol developed by the World Health Organisation.

Then the result has to be sent back to you. The result is also logged with the NICD. The process typically takes 24 to 48 hours but one laboratory doctor we spoke to on Monday said that with the massive increase in tests, the process will probably start taking longer as a backlog builds.

South Africa’s capacity

We actually have a very good testing infrastructure. The National Health Laboratory Service has laboratories across the country and there is also substantial private sector capacity. Lancet Laboratories, on Monday, published a list of 51 locations in seven provinces where people can find out their COVID-19 status.

But these labs also have to do TB, HIV and other tests. Some use sophisticated machines that can do tests for a range of diseases simultaneously, but Covid-19 is stretching capacity.

Is the price reasonable?

PCR tests are expensive. On Monday Lancet Laboratories was charging about R1,200 per test. An official at a competitor, Pathcare, told us they are charging R995. Private sector patients may be able to afford this, but most people will likely get tested by the state which doesn’t charge.

The NICD reported on 16 March that state and private laboratories had conducted 2,405 tests.

How much does it really cost a lab to do a PCR test? That’s hard to calculate because there’s the cost of the lab technician, the administrative systems and the chemical reagents and equipment. One estimate we received is that collecting the swab is about R50 and the chemical reagents cost about R100. But another estimate we received was R400.

Any which way you look at it though, the price being charged by the labs probably includes a very handsome profit. It will be interesting to see if activists put pressure on them to drop the price.

How accurate are the tests?

This is a hard question to answer. The short answer is we don’t know but probably reasonably good.

With medical diagnostics there are two measures that determine accuracy:

Specificity, which measures how good the test is at not confusing the virus with something else, causing a false positive result.

Sensitivity, which measures how good the test is at finding the virus when it’s present. Failing to find it when it’s there is a false negative.

HIV tests, for example, have very high sensitivity and specificity. They seldom give the wrong result. Commonly used TB tests on the other hand, while getting better, have quite a lot of false negatives.

The NICD does point out that there are a number of reasons that could produce a negative test in people that actually have the infection, including a poor quality sample, a sample collected too early or too late in the infection cycle, poor handling of the sample between collection and arrival in the laboratory, or the virus mutating or being suppressed for some reason. When someone who is strongly suspected of having COVID-19 tests negative, it could be for these reasons, and so a sample from the lungs may be needed.

Source: GroundUp

GroundUp is a community news organisation that focuses on social justice stories in vulnerable communities. We want our stories to make a difference.

Go to: http://www.groundup.org.za/