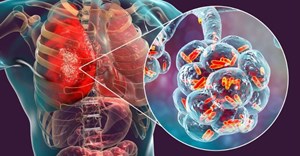

Blocking a single protein, which appears responsible for the ineffectiveness of antibiotics against some tuberculosis-causing bacteria, may help shorten treatment time for the disease.

Treatment can last for months because of persistent bacterial subpopulation, but a new study from Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health suggests that Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb)—the microbe that causes TB—can create daughter cells that are physiologically diverse, which makes them less susceptible to antibiotics.

Researchers found that Mtb without a protein called LamA formed bacteria that were far less diverse—and thus more uniformly susceptible to antibiotics.

Individual mycobacterial organisms all differ in their size and shape, even if they come from the same, genetically identical population and the efficacy of antibiotics varies among individual organisms.

The researchers set out to investigate the reasons for this variation, and how variability relates to survival of the mycobacterial population.

“We largely studied an organism called Mycobacterium smegmatis, a relative of the bacterium that causes TB, Mycobacterium tuberculosis,” said Dr Eric Rubin, Irene Heinz Given professor of immunology and infectious diseases.

The study showed that each individual mycobacterial organism in a population stained differently with a fluorescent dye. It also showed that the fluorescence intensity of individual organisms correlated closely with how quickly they were killed by rifampin, an antibiotic that is used to treat TB.

The researchers then searched for bacterial mutants that either increased or decreased staining. “Cells that lack LamA grow perfectly normally. However, they lose many of the differences that distinguish individual cells. And they are killed more uniformly by antibiotics.”