The Life Esidimeni tragedy highlights the need to review South Africa's bioethics, abandon its denial mentality and learn about true accountability.

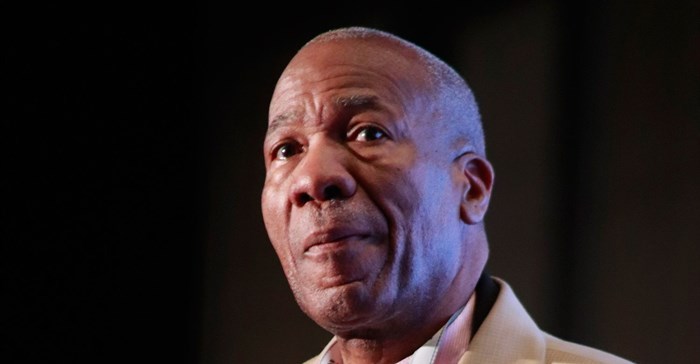

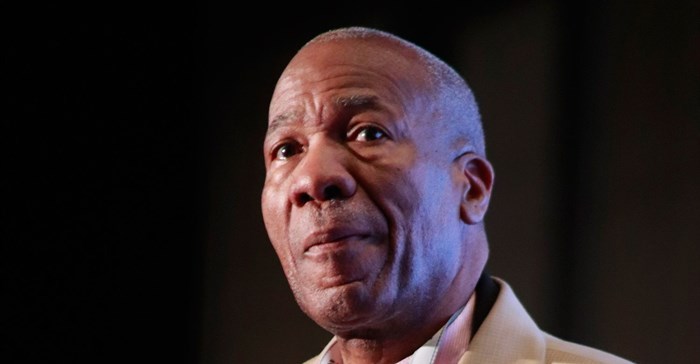

Professor Malegapuru Makgoba, the health ombudsman

“Bioethics hasn’t been reviewed for the past 50 years. We live under what I call ‘colonial and apartheid’ bioethics. When we got our independence in 1994, we did not sit down and say what kind of bioethics we need in the new country that are consistent with our human rights-based constitution," says Professor Malegapuru Makgoba, the health ombudsman.

He led the investigation into the incident which made headlines internationally. About 140 mentally ill patient died due to the Gauteng Health Department’s decision to move them to inadequate NGO facilities in 2016 to save costs. In March this year, deputy chief justice Dikgang Moseneke ordered government to pay R1.2m to families of the patients for the trauma suffered.

First lesson

According to him, the 1948 publication, The Sick African – A Clinical Study, formed the foundation of bioethics in southern Africa and is obviously colonial and outdated. The book identifies two types of African patients in Zambia. The sophisticated patient adapts habits of western civilisation while the unsophisticated seldom interacts with whites and is ignorant of, among others, cleanliness and disease prevention.

The death of Steve Biko, the ombud pointed out, is an excellent example of apartheid bioethics. Medical practitioners subdued themselves to political machinations, proclaiming that Biko's death was natural when we all know that it wasn’t.

Second lesson

When South Africans need to confront a truth, they tend to go into denial, Makgoba says. A case in point is the Aids denial under President Thabi Mbeki and the late health minister, Manto Tshabalala-Msimang – an estimated 300,000 people lost their lives due to a political decision. The cause of death was not attributed to Aids, and today there are still doctors who don’t attribute death to Aids when issuing death certificates.

“Politics prevail over and shape the practice of healthcare in South Africa in the new dispensation. We saw this in the Life Esidimeni case, where sometimes some of the death certificates where not filled in by doctors but by other people. The issue of denial is a very important part of our political make-up.”

Makgoba says that Hitler sterilised people against their wishes in the name of science and in his quest to create a ‘super race’. If you put a 'sombre thought' forward to politicians, you run the risk of being called a counter-revolutionary. Anyone who disagrees with the ruling authority becomes ‘an enemy of the state’ - this is what happened in Germany and in the Soviet Union in the past and still happens in modern states and society such as ours.

“We have a long history where science is used to underpin wrong political decisions,” says Makgoba.

Third lesson

Makgoba explains that even where there seems to be independence, there’s political interference behind the scenes – as evidenced by utterances made by the current public protector. Furthermore, there’s a failure to account. Those involved in the Life Esidimeni tragedy claimed collective responsibility, skirting the issue of personal accountability.

“In government, when you take a job as a head of department, you are appointed according to laws and you are accountable for your job,” Makgoba says. In politics you may have collective responsibility but not in government.

To ensure people are held accountable, he’d like to see jail time being served. When investigating Life Esidimeni he was asked by those under investigation, “Why do you want to make an example of us when others are forgiven?”